Making family history

Family history is not all about chasing old birth records and transcripts from past centuries. It can also be capturing more recent history - for future historians.

Recently the GSV Writers challenged themselves to write about a family photo in 350 words. Over twenty stories emerged, ranging from a well-travelled bracelet, an elopement, a tennis player and the boxer Billy Farnan. And this story below - 'Nanna loved babies' by Jackie van Bergen. The nice aspect of these stories is that they include the author's own memories.

Jackie's experience in sharing this story with her mother should encourage us to try this.

'I’m definitely spurred on by the reaction of my mother. She has been losing interest in things as her memory is failing and lockdown took away all her stimulating activities. Dad said he hadn’t seen her so animated. Mum remembered enough to keep asking when the next story was coming. Other relatives have responded with memories of their own - resulting in some stories being amended or added to.'

Nanna loved babies

There weren’t many options open to unmarried country girls in the mid 1920s. Nanna had all the accomplishments you read about in Jane Austen novels, she played the piano, wrote poetry, sewed, embroidered, made doilies, and was a whiz at cards.

Mavis Fanshawe Long (1906-1982) and her sister Frances Jean McVey Long (1901-1988) moved to the city and trained at the Foundling Hospital and Infants’ Home in Berry Street, East Melbourne and Beaconsfield. In November 1932, she was awarded a certificate recognising completion of her probationer training, and in February 1933 received her certificate of competency as a Mothercraft Nurse from the Department of Public Health.

The Berry Street hospital was founded in 1877 by a group of Melbourne women with the help of the wife of the Governor of the time. The aim was to support unwed, isolated or rejected mothers and their children. In 1907 they implemented a formalised mothercraft nurse training program that continued until 1975. Starting in 2006, the Berry Street organisation issued apologies related to their role in the stolen generations, in forced adoptions, and for any abuse or neglect suffered by those in their care.

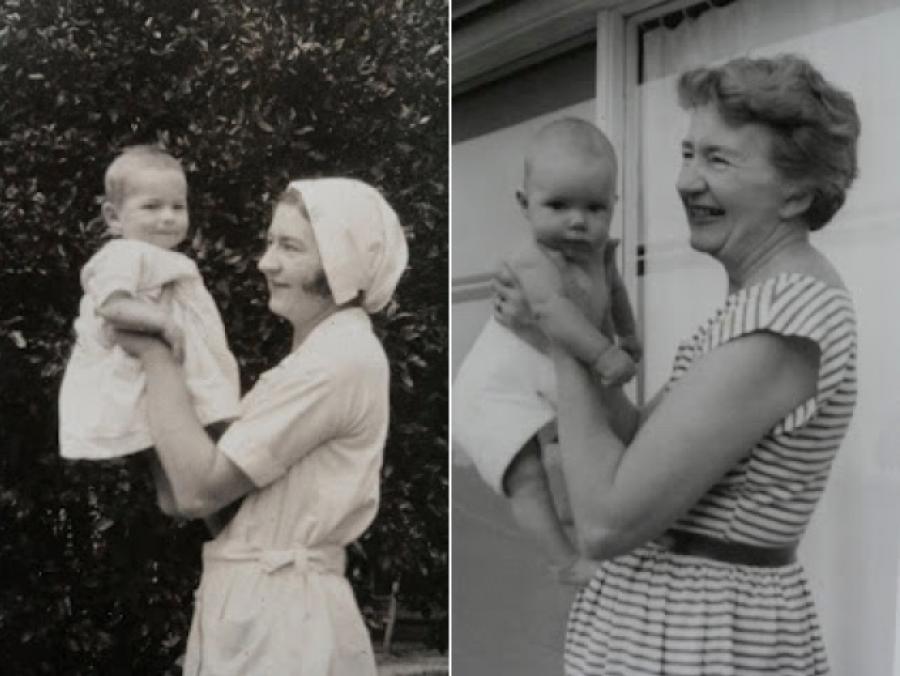

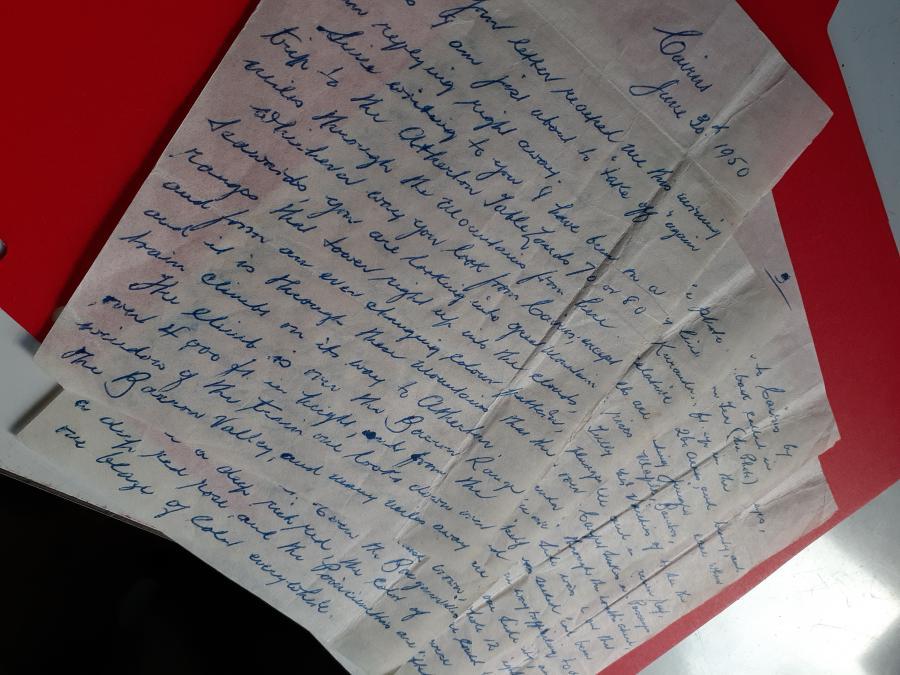

Nanna obviously loved her time working at East Melbourne and Beaconsfield, as she kept many mementos such as photos of the babies and nurses, and booklets (see photo on the left). It was at Berry Street that Nanna befriended Shirley Constance Garrett (1912-1978), a fellow nurse from St Kilda. It was through Shirley and visiting her family that Nanna met her husband, Shirley’s brother John Raikes Garrett (1908-1992). They married in 1935. Nanna’s first baby was born in 1937, and her second in 1939.

Mum says Nanna couldn’t get enough of us when we were little. I was her first grandchild (see photo on the right), and was thoroughly spoiled, not that she didn’t spoil all of us.

I’m sorry I didn’t have the chance to get to know this lovely gentle lady when I was an adult. It’s a shame so many kids these days live so far away from their grandparents – they are missing out on all those stories, and all that love.

Jackie van Bergen, September 2021

***

Photo credits

Left. Mavis Long, at Berry Street Home, 1932

Right. 'Nanna' (Mavis) with author, 1960 (photos in possession of author).

On Monday March 23 it was decided that the GSV Centre, both the library and the office, would close from today Wed March 25 until further notice.

On Monday March 23 it was decided that the GSV Centre, both the library and the office, would close from today Wed March 25 until further notice.